Chapter 1: The History of Monetary Systems

"By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some."

— John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919)

Overview

Keynes wrote these words a century ago, describing the aftermath of World War I. The mechanisms have grown more sophisticated since then, but the underlying dynamic remains: monetary systems encode power relationships. Those who control the creation and distribution of money enjoy structural advantages that compound over time.

This chapter traces the evolution of monetary systems—from commodity money through metallic standards, the Bretton Woods order, and into the current fiat era—with particular attention to the power relationships embedded in each. The goal is not to assign blame but to understand mechanics: how did we arrive at the current system, what alternatives were considered and rejected, and what patterns emerge from this history?

Understanding these patterns is prerequisite to evaluating any alternative proposal, including the energy-backed currency explored in subsequent chapters.

Chapter Structure:

- Pre-Modern Money — Global overview of early monetary forms

- Metallic Standards — The gold standard era and its lessons

- Bretton Woods — The postwar order, Keynes's alternative, and its collapse

- Fiat/Dollar Hegemony — The current system's mechanics

- Alternative Paths — The SDR, yuan internationalization, and other proposals

- Bridge to Energy — What this history suggests about better backing

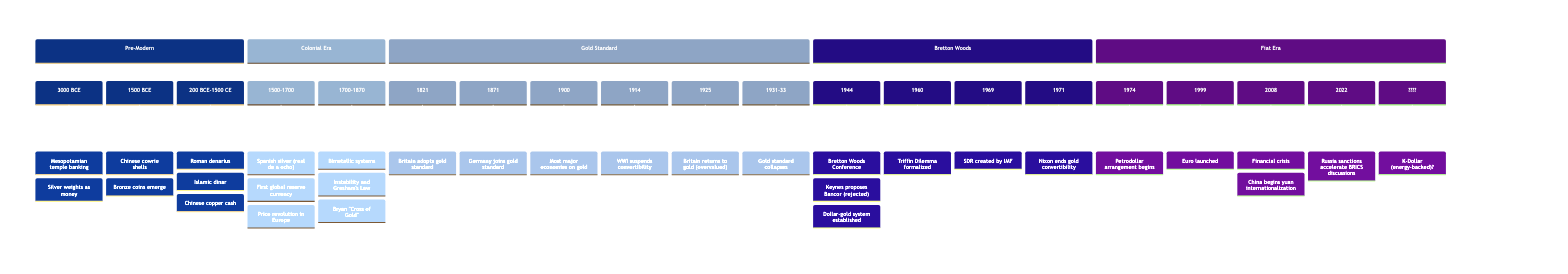

Figure 1.1: Timeline of global monetary systems from ancient temple banking to the present fiat era.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of global monetary systems from ancient temple banking to the present fiat era.

1.1 Pre-Modern Money

Before examining Western monetary history in detail, it's worth noting that money emerged independently across multiple civilizations—and the pattern is consistent: money is an artifact of power.

Global Origins

China: Cowrie shells served as currency as early as 1500 BCE, eventually replaced by bronze coins during the Zhou Dynasty. By the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), China pioneered paper money—jiaozi—backed by the state's promise. The pattern held: those who controlled the mint controlled wealth flows.

Africa: The cowrie shell, indigenous to the Maldives, became currency across West Africa via trans-Saharan trade. By the 19th century, millions of cowries circulated in what is now Nigeria. The supply was controlled by long-distance traders and, later, European colonial powers who deliberately inflated the cowrie supply to extract resources.

Pacific: The Rai stones of Yap—massive limestone discs weighing up to 4 tons—demonstrate that money's value derives from social consensus, not portability. Ownership was tracked communally; the stones themselves rarely moved. The power to adjudicate ownership disputes conferred monetary power.

Mesopotamia: Temple complexes in Sumer (3000 BCE) served as early central banks, issuing standardized weights of silver and maintaining accounts of debts and credits. Priests controlled the monetary system; the economic and the sacred were inseparable.

The Pattern

Across these examples, a common structure emerges:

- Money originates from power centers—temples, states, trading networks

- Control of money supply confers wealth extraction capability

- Social consensus matters more than physical properties

- Changes in monetary systems accompany changes in power

This pattern will repeat through the gold standard, Bretton Woods, and the fiat era.

A Note on Origins

The textbook story—that money evolved from barter to solve the "double coincidence of wants" problem—is largely a myth. Anthropological evidence suggests that credit, debt, and social obligation preceded coinage. David Graeber's Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011) provides a comprehensive critique of the barter narrative. This matters because it suggests money is fundamentally a social and political technology, not merely an economic convenience.

1.2 Metallic Standards

Spanish Silver: The First Global Currency

The Spanish real de a ocho (piece of eight) became the world's first global reserve currency in the 16th century, flowing from New World mines through Manila and Seville to markets worldwide. Spain's monetary power derived directly from control of American silver—a pattern that foreshadows later arrangements.

The Spanish experience also demonstrates the risks of commodity money: the massive influx of New World silver contributed to the "price revolution" in Europe, with inflation rates of 1-2% annually—modest by modern standards but unprecedented for the era. Control of the money supply, even when that money was metal, conferred power over prices across continents.

Bimetallism's Instabilities

Before the gold standard, most nations operated on bimetallic systems—gold and silver at fixed exchange ratios. The problems were predictable: when market ratios diverged from official ratios, one metal would be hoarded while the other circulated (Gresham's Law). The United States fought political battles over this issue throughout the 19th century, culminating in William Jennings Bryan's famous "Cross of Gold" speech in 1896.

The bimetallic experience taught a lesson: fixed ratios between different forms of money are difficult to maintain when underlying values shift. This will become relevant when considering energy-backed currency, where multiple energy forms must somehow be made fungible.

The Classical Gold Standard (1870-1914)

Britain's adoption of the gold standard in 1821, followed by Germany in 1871, created pressure for convergence. By 1900, most major economies had adopted gold backing.

What Worked:

- Price stability: Wholesale prices in Britain were roughly the same in 1914 as in 1815

- International trade facilitation: Fixed exchange rates reduced transaction costs

- Credibility: Central banks had limited discretion, which constrained inflationary temptations

- Automatic adjustment: Trade deficits led to gold outflows, monetary contraction, falling prices, and eventual correction

What Failed:

- Deflation pressure: Economic growth exceeded gold supply growth, creating persistent downward pressure on prices

- Procyclical policy: The adjustment mechanism amplified rather than dampened business cycles

- Unequal distribution: Countries without gold mines had to export real goods to obtain money

- Rigidity: The system couldn't accommodate the massive fiscal demands of World War I

The gold standard's end came not from its internal contradictions but from external shock. The costs of World War I exceeded what any gold-backed system could finance. Countries suspended convertibility one by one, and the pre-1914 order never fully returned.

Interwar Instability (1919-1939)

The attempt to restore the gold standard after World War I produced what economists call the "gold exchange standard"—a fragile hybrid where currencies were backed by both gold and foreign exchange reserves. Britain's return to gold at the pre-war parity in 1925, championed by Winston Churchill as Chancellor of the Exchequer, overvalued the pound and contributed to chronic unemployment throughout the 1920s.

The system's fragility became apparent in 1929-1931. As capital fled from weaker economies to stronger ones, the adjustment mechanism became a feedback loop of deflation. Countries that left the gold standard earlier—Britain in 1931, the United States in 1933—recovered faster than those that held on.

Keynes observed this closely. His General Theory (1936) was, in part, a response to the gold standard's failures. His later Bretton Woods proposal would attempt to address the fundamental problem: in a system of fixed exchange rates, the burden of adjustment falls entirely on deficit countries, while surplus countries face no pressure to adjust.

1.3 Bretton Woods: Order and Collapse (1944-1971)

The 1944 Negotiations

As World War II neared its end, 44 allied nations gathered at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to design a new monetary order. Two competing visions dominated the negotiations.

The British Plan (Keynes): An International Clearing Union that would issue its own currency—the bancor—for settling international accounts. Countries would hold bancor balances rather than dollars or gold. Crucially, Keynes proposed that both deficit and surplus countries face adjustment pressure. Surplus nations accumulating too many bancors would be taxed, creating incentive for balanced trade.

The American Plan (White): A system centered on the dollar, with the dollar tied to gold at $35 per ounce and other currencies tied to the dollar. The International Monetary Fund would provide short-term financing for countries facing balance-of-payments difficulties, but adjustment pressure would fall primarily on deficit countries.

Why Bancor Lost

The American plan prevailed for straightforward reasons: the United States emerged from World War II with 70% of the world's monetary gold and half its manufacturing capacity. Keynes later remarked that the negotiations weren't really about the merits of the proposals; America could dictate terms.

The bancor's defeat merits reflection because it represented a path not taken. Keynes had diagnosed the fundamental problem of any reserve currency system: the issuing country faces conflicting obligations. To provide global liquidity, it must run trade deficits—exporting its currency to the world. But persistent deficits eventually undermine confidence in the currency itself.

This was not an abstract concern. It would materialize precisely as Keynes predicted, though he did not live to see it.

The Triffin Dilemma

Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin formalized this problem in 1960. For the dollar to serve as global reserve currency, the United States had to supply dollars to the world—which meant running balance-of-payments deficits. But persistent deficits would eventually exhaust confidence in dollar-gold convertibility.

The system contained its own destruction: success required behavior that guaranteed eventual failure.

By the late 1960s, foreign dollar holdings far exceeded US gold reserves. France, under de Gaulle, began converting dollars to gold—exercising a right that was technically available to all but practically destabilizing. The system was under pressure.

Nixon and the End of Convertibility

Richard Nixon ended dollar-gold convertibility on August 15, 1971, in what his administration called the "New Economic Policy." The immediate trigger was British and French requests to convert dollars to gold, but the underlying cause was the Triffin dilemma playing out as predicted.

Nixon's decision—made on a weekend at Camp David, without consulting international partners—demonstrated a fundamental asymmetry: the reserve currency issuer could unilaterally change the rules. Other countries had to adjust; America could dictate.

Treasury Secretary John Connally captured the dynamic: "The dollar is our currency, but it's your problem."

This was not the end of dollar hegemony—it was its metamorphosis. Freed from gold's constraints, the dollar-based system would become both more flexible and more explicitly dependent on American power.

1.4 The Fiat Era: Dollar Hegemony Without Gold

Petrodollar Mechanics

The dollar's post-1971 position was secured by a new arrangement. In 1974, following the oil shock, Saudi Arabia agreed to price oil exclusively in dollars and to invest surplus petrodollars in US Treasury securities. In exchange, the United States provided security guarantees.

This created a self-reinforcing system:

- Oil-importing countries must acquire dollars to buy oil

- Oil-exporting countries accumulate dollar reserves

- Those reserves flow back to US financial markets

- This demand supports dollar value and finances US deficits

Other oil producers followed Saudi Arabia's lead. By 1975, OPEC as a whole was pricing oil in dollars. The commodity backing had changed—from gold to oil—but the result was similar: demand for dollars was structurally embedded in the global economy.

Reserve Currency Privilege

The US dollar now serves as:

- Unit of account: Oil, commodities, most international contracts

- Medium of exchange: Approximately 88% of foreign exchange transactions involve dollars

- Store of value: Approximately 59% of identified global reserves are dollar-denominated

Seigniorage at Scale

Classical seigniorage is the profit from minting coins—the difference between face value and production cost. Modern seigniorage operates differently.

The United States creates dollars—physical and electronic—at near-zero marginal cost. The rest of the world must provide real goods, services, or assets to obtain them. The difference represents a wealth transfer.

Quantifying this transfer is methodologically contested, but estimates of the annual benefit to the United States range from $100 billion to several hundred billion dollars. (See Issue A2 for detailed analysis.)

Inflation Distribution

When the Federal Reserve expands the money supply:

- New dollars enter circulation

- Dollar holders worldwide experience proportional dilution

- Approximately 60% of physical dollars circulate outside the United States

- A majority of dollar-denominated debt is held outside the United States

The distribution of inflation costs is global, but representation in monetary policy is national. Non-Americans bear costs of Federal Reserve decisions without voice in those decisions.

Financial Infrastructure as Instrument

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) routes the majority of international payments. While technically a Belgian cooperative, the United States exercises significant influence over its operations.

Exclusion from SWIFT creates severe economic isolation. Iran was excluded from 2012-2016 and again from 2018. Russian banks were excluded following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. These sanctions demonstrate that access to the dollar-based financial system is not a neutral public good but a contingent privilege.

System Stability and Its Costs

The dollar system provides genuine benefits:

- Liquidity: Deep markets reduce transaction costs

- Stability: The dollar has been less volatile than alternatives

- Network effects: Universal acceptance reduces coordination problems

These benefits create lock-in. Even countries that understand the structural asymmetries find alternatives costly. The collective action problem is severe: any individual country that defects from the dollar system faces costs, while benefits of an alternative require coordinated adoption.

The system is stable in part because its costs are distributed and difficult to observe. A farmer in Indonesia experiences currency volatility and input price changes without necessarily connecting these to Federal Reserve policy or the structure of the international monetary system.

1.5 Alternative Paths Not Taken

The dollar system has faced challenges. Understanding why alternatives have struggled illuminates the structural barriers any new proposal must overcome.

The SDR: Potential Unrealized

The Special Drawing Right (SDR) was created by the IMF in 1969 specifically to address the Triffin dilemma. If global liquidity needs could be met by an international asset rather than national currencies, the reserve currency issuer would no longer face conflicting obligations.

The SDR is valued against a basket of currencies (currently: dollar 43.4%, euro 29.3%, yuan 12.3%, yen 7.6%, pound 7.4%). Countries can exchange SDRs for usable currency through the IMF.

What the SDR could have become:

- A genuine international reserve asset, reducing dependence on the dollar

- A mechanism for creating liquidity without US balance-of-payments deficits

- A more symmetric system, as Keynes had envisioned

Why it stalled:

- Limited issuance: Only SDR 660 billion ($943 billion) exist—a fraction of dollar reserves

- No private use: SDRs cannot be used in private transactions, limiting their utility

- Governance constraints: Major SDR allocations require 85% approval; the US holds 16.5% of votes (effective veto)

- US opposition: Expanding the SDR would reduce dollar privilege, which the US has no incentive to accept

The SDR remains a technical success and a political non-starter. It demonstrates that the barriers to reform are not primarily technical but political: the beneficiary of the current system has veto power over changes.

Yuan Internationalization

China has pursued yuan internationalization since the 2008 financial crisis exposed risks of dollar dependence. Elements of this effort include:

- Bilateral currency swap agreements with over 40 countries

- Yuan-denominated oil futures launched in 2018

- Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) as alternative to SWIFT

- Belt and Road Initiative financing in yuan

Results have been modest:

- The yuan represents approximately 2.3% of global reserves (vs. 59% for dollar)

- Yuan share of global payments: approximately 3.6%

- Most yuan trade settles in Hong Kong, not mainland China

Structural barriers:

- Capital controls: China maintains controls that limit yuan convertibility

- Rule of law concerns: Foreign holders worry about arbitrary policy changes

- Network effects: Switching costs favor incumbents

- US countermeasures: Sanctions risk for yuan-based transactions in some contexts

China faces a dilemma: the controls that give it policy autonomy also limit international adoption. The dollar's dominance was built on deep, liquid, open markets—characteristics China is unwilling to fully replicate.

BRICS and Multipolarity

Following Western sanctions on Russia in 2022, BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa—now expanded) accelerated discussions of dollar alternatives. Proposals range from increased local currency trade to a potential BRICS reserve currency.

Fundamental challenges:

- Heterogeneous interests: China runs surpluses; India runs deficits. Their monetary interests differ.

- Trust deficits: Participating nations don't fully trust each other

- Infrastructure gap: No BRICS equivalent to dollar financial infrastructure exists

- Technical complexity: A basket currency of countries with vastly different economies is difficult to design

These discussions reveal a genuine desire for alternatives but limited capacity to create them. The dollar system persists not because it is optimal but because replacing it requires solving coordination problems that have, so far, proven intractable.

Why Alternatives Fail

Three factors interact:

Network effects: The dollar's dominance is self-reinforcing. Exporters invoice in dollars because importers can pay in dollars because banks hold dollars because central banks reserve dollars. Breaking this cycle requires coordinated switching by millions of actors—a classic collective action problem.

Active US position: The United States has significant capacity to impose costs on challengers. Sanctions, financial pressure, and diplomatic leverage raise the price of defection. Countries considering alternatives must weigh uncertain future benefits against immediate costs.

Design flaws in alternatives: Each challenger has specific weaknesses:

- SDR: Limited issuance, no private use, governance constraints

- Yuan: Capital controls, rule of law concerns

- BRICS: Heterogeneous interests, trust deficits

The combination is formidable. Network effects create inertia, design flaws limit alternatives' attractiveness, and US power raises switching costs. Any successful alternative must address all three.

1.6 Bridge to Energy: Patterns and Possibilities

What patterns emerge from this history?

Power Transitions

| Era | Dominant Currency | Issuing Power | Who Gained | Who Bore Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1500-1700 | Spanish silver | Spain | Spanish Crown, silver miners | European consumers (inflation), indigenous Americans |

| 1870-1914 | Pound sterling | Britain | London financiers, British exporters | Agrarian economies, gold-poor nations |

| 1944-1971 | Dollar (gold-backed) | United States | US government, dollar holders | Deficit countries forced to adjust |

| 1971-present | Dollar (fiat) | United States | US consumers, dollar issuers | Dollar holders abroad (inflation), sanctions targets |

Each transition created new winners and losers. The pattern is not conspiracy but structure: the architecture of the monetary system determines who benefits from its operation.

Consistent Dynamics

-

Money follows power: Spanish silver, British gold, American dollars—each monetary era reflected the dominant power of its time. Monetary transitions accompanied geopolitical transitions.

-

Backings fail or are abandoned: Commodity money gave way to metallic standards. Gold backing was suspended during crises and ultimately abandoned. Even the implicit petrodollar backing is now contested. No backing has proven permanent.

-

The issuer extracts: Whether through seigniorage, inflation export, or financial infrastructure control, the issuer of the dominant currency gains structural advantages. This is not corruption or conspiracy—it is the predictable consequence of the system's design.

-

Alternatives face high barriers: Network effects, vested interests, and collective action problems make transitions rare and typically crisis-driven.

Requirements for an Alternative

If history is a guide, a successful alternative to the dollar would need:

- Intrinsic value: Something that justifies demand independent of network effects, reducing coordination problems

- Distributed issuance: No single nation controlling supply, eliminating single-issuer extraction

- Technical credibility: Verifiable, manipulation-resistant mechanisms

- Crisis trigger: A shock that makes switching costs acceptable compared to status quo costs

Gold had intrinsic value but limited supply. Fiat has unlimited supply but arbitrary value. The SDR has neither intrinsic value nor meaningful supply. The yuan has supply but limited international trust.

Is there a backing that combines intrinsic value with scalable supply? That distributes issuance rather than concentrating it? That grows with economic activity rather than lagging behind it?

The next chapter examines energy as a candidate.

Key Takeaways

-

Money encodes power: Every monetary system reflects and reinforces the power structure that created it. Transitions in monetary regimes accompany transitions in geopolitical power.

-

Backings matter, then fail: Gold provided stability but couldn't scale with economic growth. The dollar provided liquidity but concentrated privilege. Each backing solved some problems while creating others.

-

The reserve currency issuer extracts: Whether through seigniorage, inflation export, or financial infrastructure control, structural advantages accrue to the issuer. This is inherent to the design, not an aberration.

-

Alternatives face triple barriers: Network effects create inertia. Design flaws limit alternatives' appeal. Incumbent power raises switching costs. Any successful alternative must address all three.

-

Keynes was right: His bancor proposal addressed the fundamental problem—the Triffin dilemma—that eventually destroyed Bretton Woods. The path not taken remains instructive.

Further Reading

- Eichengreen, B. (2011). Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar

- Steil, B. (2013). The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order

- Graeber, D. (2011). Debt: The First 5,000 Years

- Triffin, R. (1960). Gold and the Dollar Crisis

- Kindleberger, C. (1973). The World in Depression, 1929-1939

- Varoufakis, Y. (2016). And the Weak Suffer What They Must?

Discussion Questions

- Could the Triffin dilemma be solved within a single-nation reserve currency framework, or is distributed issuance the only solution?

- What crisis scenarios might create the conditions for a monetary transition?

- If Keynes's bancor had been adopted, how might the post-war era have unfolded differently?

- The petrodollar system implicitly backs the dollar with energy access. What would explicit energy backing change?

Next: Chapter 2: Why Energy?